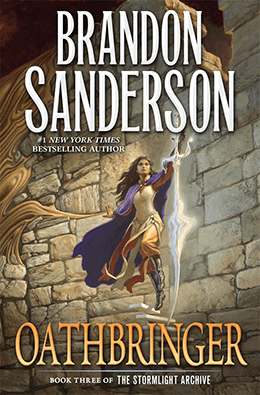

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 31

Demands of the Storm

If they cannot make you less foolish, at least let them give you hope.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Throughout his youth, Kaladin had dreamed of joining the military and leaving quiet little Hearthstone. Everyone knew that soldiers traveled extensively and saw the world.

And he had. He’d seen dozens upon dozens of empty hills, weed-covered plains, and identical warcamps. Actual sights, though… well, that was another story.

The city of Revolar was, as his hike with the parshmen had proven, only a few weeks away from Hearthstone by foot. He’d never visited. Storms, he’d never actually lived in a city before, unless you counted the warcamps.

He suspected most cities weren’t surrounded by an army of parshmen as this one was.

Revolar was built in a nice hollow on the leeward side of a series of hills, the perfect spot for a little town. Except this was not a “little town.” The city had sprawled out, filling in the areas between the hills, going up the leeward slopes—only leaving the tips completely bare.

He’d expected a city to look more organized. He’d imagined neat rows of houses, like an efficient warcamp. This looked more like a snarl of plants clumped in a chasm at the Shattered Plains. Streets running this way and that. Markets that poked out haphazardly.

Kaladin joined his team of parshmen as they wound along a wide roadway kept level with smoothed crem. They passed through thousands upon thousands of parshmen camped here, and more gathered by the hour, it seemed.

His, however, was the only group that carried stone-headed spears on their shoulders, packs of dried grain biscuits, and hogshide leather sandals. They tied their smocks with belts, and carried stone knives, hatchets, and tinder in waxed sleeves made from candles he’d traded for. He’d even begun teaching them to use a sling.

He probably shouldn’t have shown them any of these things; that didn’t stop him from feeling proud as he walked with them, entering the city.

Crowds thronged the streets. Where had all these parshmen come from? This was a force of at least forty or fifty thousand. He knew most people ignored parshmen… and, well, he’d done the same. But he’d always had tucked into the back of his mind this idea that there weren’t that many out there. Each high-ranking lighteyes owned a handful. And a lot of the caravaneers. And, well, even the less wealthy families from cities or towns had them. And there were the dockworkers, the miners, the water haulers, the packmen they used when building large projects.…

“It’s amazing,” Sah said from where he walked beside Kaladin, carrying his daughter on his shoulder to give her a better view. She clutched some of his wooden cards, holding them close like another child might carry a favorite stuffed doll.

“Amazing?” Kaladin asked Sah.

“Our own city, Kal,” he whispered. “During my time as a slave, barely able to think, I still dreamed. I tried to imagine what it would be like to have my own home, my own life. Here it is.”

The parshmen had obviously moved into homes along the streets here. Were they running markets too? It raised a difficult, unsettling question. Where were all the humans? Khen’s group walked deeper into the city, still led by the unseen spren. Kaladin spotted signs of trouble. Broken windows. Doors that no longer latched. Some of that would be from the Everstorm, but he passed a couple of doors that had obviously been hacked open with axes.

Looting. And ahead stood an inner wall. It was a nice fortification, right in the middle of the city sprawl. It probably marked the original city boundary, as decided upon by some optimistic architect.

Here, at long last, Kaladin found signs of the fight he’d expected during his initial trip to Alethkar. The gates to the inner city lay broken. The guardhouse had been burned, and arrowheads still stuck from some of the wood beams they passed. This was a conquered city.

But where had the humans been moved? Should he be looking for a prison camp, or a heaping pyre of burned bones? Considering the idea made him sick.

“Is this what it’s about?” Kaladin said as they walked down a roadway in the inner city. “Is this what you want, Sah? To conquer the kingdom? Destroy humankind?”

“Storms, I don’t know,” he said. “But I can’t be a slave again, Kal. I won’t let them take Vai and imprison her. Would you defend them, after what they did to you?”

“They’re my people.”

“That’s no excuse. If one of ‘your people’ murders another, don’t you put them in prison? What is a just punishment for enslaving my entire race?”

Syl soared past, her face peeking from a shimmering haze of mist. She caught his eye, then zipped over to a windowsill and settled down, taking the shape of a small rock.

“I…” Kaladin said. “I don’t know, Sah. But a war to exterminate one side or the other can’t be the answer.”

“You can fight alongside us, Kal. It doesn’t have to be about humans against parshmen. It can be nobler than that. Oppressed against the oppressors.”

As they passed the place where Syl was, Kaladin swept his hand along the wall. Syl, as they’d practiced, zipped up the sleeve of his coat. He could feel her, like a gust of wind, move up his sleeve then out his collar, into his hair. The long curls hid her, they’d determined, well enough.

“There are a lot of those yellow-white spren here, Kaladin,” she whispered. “Zipping through the air, dancing through buildings.”

“Any signs of humans?” Kaladin whispered.

“To the east,” she said. “Crammed into some army barracks and old parshman quarters. Others are in big pens, watched under guard. Kaladin… there’s another highstorm coming today.”

“When?”

“Soon, maybe? I’m new to guessing this. I doubt anyone is expecting it. Everything has been thrown off; the charts will all be wrong until people can make new ones.”

Kaladin hissed slowly through his teeth.

Ahead, his team approached a large group of parshmen. Judging by the way they’d been organized into large lines, this was some kind of processing station for new arrivals. Indeed, Khen’s band of a hundred was shuffled into one of the lines to wait.

Ahead of them, a parshman in full carapace armor—like a Parshendi— strolled down the line, holding a writing board. Syl pulled farther into Kaladin’s hair as the Parshendi man stepped up to Khen’s group.

“What towns, work camps, or armies do you all come from?” His voice had a strange cadence, similar to the Parshendi Kaladin had heard on the Shattered Plains. Some of those in Khen’s group had hints of it, but nothing this strong.

The scribe parshman wrote down the list of towns Khen gave him, then noted their spears. “You’ve been busy. I’ll recommend you for special training. Send your captive to the pens; I’ll write down a description here, and once you’re settled, you can put him to work.”

“He…” Khen said, looking at Kaladin. “He is not our captive.” She seemed begrudging. “He was one of the humans’ slaves, like us. He wishes to join and fight.”

The parshman looked up in the air at nothing.

“Yixli is speaking for you,” Sah whispered to Kaladin. “She sounds impressed.”

“Well,” the scribe said, “it’s not unheard of, but you’ll have to get permission from one of the Fused to label him free.”

“One of the what?” Khen asked.

The parshman with the writing board pointed toward his left. Kaladin had to step out of the line, along with several of the others, to see a tall parshwoman with long hair. There was carapace covering her cheeks, running back along the cheekbones and into her hair. The skin on her arms prickled with ridges, as if there were carapace under the skin as well. Her eyes glowed red.

Kaladin’s breath caught. Bridge Four had described these creatures to him, the strange Parshendi they’d fought during their push toward the center of the Shattered Plains. These were the beings who had summoned the Everstorm.

This one focused directly on Kaladin. There was something oppressive about her red gaze.

Kaladin heard a clap of thunder in the far distance. Around him, many of the parshmen turned toward it and began to mutter. Highstorm.

In that moment, Kaladin made his decision. He’d stayed with Sah and the others as long as he dared. He’d learned what he could. The storm presented a chance.

It’s time to go.

The tall, dangerous creature with the red eyes—the Fused, they had called her—began walking toward Khen’s group. Kaladin couldn’t know if she recognized him as a Radiant, but he had no intention of waiting until she arrived. He’d been planning; the old slave’s instincts had already decided upon the easiest way out.

It was on Khen’s belt.

Kaladin sucked in the Stormlight, right from her pouch. He burst alight with its power, then grabbed the pouch—he’d need those gemstones—and yanked it free, the leather strap snapping.

“Get your people to shelter,” Kaladin said to the surprised Khen. “A highstorm is close. Thank you for your kindness. No matter what you are told, know this: I do not wish to be your enemy.”

The Fused began to scream with an angry voice. Kaladin met Sah’s betrayed expression, then launched himself into the air.

Freedom.

Kaladin’s skin shivered with joy. Storms, how he’d missed this. The wind, the openness above, even the lurch in his stomach as gravity let go. Syl spun around him as a ribbon of light, creating a spiral of glowing lines. Gloryspren burst up about Kaladin’s head.

Syl took on the form of a person just so she could glower at the little bobbing balls of light. “Mine,” she said, swatting one of them aside.

About five or six hundred feet up, Kaladin changed to a half Lashing, so he slowed and hovered in the sky. Beneath, that red-eyed parshwoman was gesturing and screaming, though Kaladin couldn’t hear her. Storms. He hoped this wouldn’t mean trouble for Sah and the others.

He had an excellent view of the city—the streets filled with figures, now making for shelter in buildings. Other groups rushed to the city from all directions. Even after spending so much time with them, his first reaction was one of discomfort. So many parshmen together in one place? It was unnatural.

This impression bothered him now as it never would have before.

He eyed the stormwall, which he could see approaching in the far distance. He still had time before it arrived.

He’d have to fly up above the storm to avoid being caught in its winds. But then what?

“Urithiru is out there somewhere, to the west,” Kaladin said. “Can you guide us there?”

“How would I do that?”

“You’ve been there before.”

“So have you.”

“You’re a force of nature, Syl,” Kaladin said. “You can feel the storms. Don’t you have some kind of… location sense?”

“You’re the one from this realm,” she said, batting away another gloryspren and hanging in the air beside him, folding her arms. “Besides, I’m less a force of nature and more one of the raw powers of creation transformed by collective human imagination into a personification of one of their ideals.” She grinned at him.

“Where did you come up with that?”

“Dunno. Maybe I heard it somewhere once. Or maybe I’m just smart.”

“We’ll have to make for the Shattered Plains, then,” Kaladin said. “We can strike out for one of the larger cities in southern Alethkar, swap gemstones there, and hopefully have enough to hop over to the warcamps.”

That decided, he tied his gemstone pouch to his belt, then glanced down and tried to make a final estimate of troop numbers and parshman fortifications. It felt odd to not worry about the storm, but he’d just move up over it once it arrived.

From up here, Kaladin could see the great trenches cut into the stones to divert away floodwaters after a storm. Though most of the parshmen had fled for shelter, some remained below, craning necks and staring up at him. He read betrayal in their postures, though he couldn’t even tell if these were members of Khen’s group or not.

“What?” Syl asked, alighting on his shoulder.

“I can’t help but feel a kinship to them, Syl.”

“They conquered the city. They’re Voidbringers.”

“No, they’re people. And they’re angry, with good reason.” A gust of wind blew across him, making him drift to the side. “I know that feeling. It burns in you, worms inside your brain until you forget everything but the injustice done to you. It’s how I felt about Elhokar. Sometimes a world of rational explanations can become meaningless in the face of that all-consuming desire to get what you deserve.”

“You changed your mind about Elhokar, Kaladin. You saw what was right.”

“Did I? Did I find what was right, or did I just finally agree to see things the way you wanted?”

“Killing Elhokar was wrong.”

“And the parshmen on the Shattered Plains that I killed? Murdering them wasn’t wrong?”

“You were protecting Dalinar.”

“Who was assaulting their homeland.”

“Because they killed his brother.”

“Which, for all we know, they did because they saw how King Gavilar and his people treated the parshmen.” Kaladin turned toward Syl, who sat on his shoulder, one leg tucked beneath her. “So what’s the difference, Syl? What is the diff rence between Dalinar attacking the parshmen, and these parshmen conquering that city?”

“I don’t know,” she said softly.

“And why was it worse for me to let Elhokar be killed for his injustices than it was for me to actively kill parshmen on the Shattered Plains?”

“One is wrong. I mean, it just feels wrong. Both do, I guess.”

“Except one nearly broke my bond, while the other didn’t. The bond isn’t about what’s right and wrong, is it, Syl. It’s about what you see as right and wrong.”

“What we see,” she corrected. “And about oaths. You swore to protect Elhokar. Tell me that during your time planning to betray Elhokar, you didn’t—deep down—think you were doing something wrong.”

“Fine. But it’s still about perception.” Kaladin let the winds blow him, feeling a pit open in his belly. “Storms, I’d hoped… I’d hoped you could tell me, give me an absolute right. For once, I’d like my moral code not to come with a list of exceptions at the end.”

She nodded thoughtfully.

“I’d have expected you to object,” Kaladin said. “You’re a… what, embodiment of human perceptions of honor? Shouldn’t you at least think you have all the answers?”

“Probably,” she said. “Or maybe if there are answers, I should be the one who wants to find them.”

The stormwall was now fully visible: the great wall of water and refuse pushed by the oncoming winds of a highstorm. Kaladin had drifted along with the winds away from the city, so he Lashed himself eastward until they floated over the hills that made up the city’s windbreak. Here, he spotted something he hadn’t seen earlier: pens full of great masses of humans.

The winds blowing in from the east were growing stronger. However, the parshmen guarding the pens were just standing there, as if nobody had given them orders to move. The first rumblings of the highstorm had been distant, easy to miss. They’d notice it soon, but that might be too late.

“Oh!” Syl said. “Kaladin, those people!”

Kaladin cursed, then dropped the Lashing holding him upward, which made him fall in a rush. He crashed to the ground, sending out a puff of glowing Stormlight that expanded from him in a ring.

“Highstorm!” he shouted at the parshman guards. “Highstorm coming!

Get these people to safety!”

They looked at him, dumbfounded. Not a surprising reaction. Kaladin summoned his Blade, shoving past the parshmen and leaping up onto the pen’s low stone wall, for keeping hogs.

He held aloft the Sylblade. Townspeople swarmed to the wall. Cries of “Shardbearer” rose.

“A highstorm is coming!” he shouted, but his voice was quickly lost in the tumult of voices. Storms. He had little doubt that the Voidbringers could handle a group of rioting townsfolk.

He sucked in more Stormlight, raising himself into the air. That quieted them, even drove them backward.

“Where did you shelter,” he demanded in a loud voice, “when the last storms came?”

A few people near the front pointed at the large bunkers nearby. For housing livestock, parshmen, and even travelers during storms. Could those hold an entire town’s worth of people? Maybe if they crowded in.

“Get moving!” Kaladin said. “A storm will be here soon.”

Kaladin, Syl’s voice said in his mind. Behind you.

He turned and found parshman guards approaching his wall with spears. Kaladin hopped down as the townspeople finally reacted, climbing the walls, which were barely chest high and slathered with smooth, hardened crem.

Kaladin took one step toward the parshmen, then swiped his Blade, separating their spearheads from the hafts. The parshmen—who had barely more training than the ones he’d traveled with—stepped back in confusion.

“Do you want to fight me?” Kaladin asked them.

One shook her head.

“Then see that those people don’t trample each other in their haste to get to safety,” Kaladin said, pointing. “And keep the rest of the guards from attacking them. This isn’t a revolt. Can’t you hear the thunder, and feel the wind picking up? ”

He launched himself onto the wall again, then waved for the people to move, shouting orders. The parshman guards eventually decided that instead of fighting a Shardbearer, they’d risk getting into trouble for doing what he said. Before too long, he had an entire team of them prodding the humans—often less gently than he’d have liked—toward the storm bunkers.

Kaladin dropped down beside one of the guards, a female whose spear he’d sliced in half. “How did this work the last time the storm hit?”

“We mostly left the humans to themselves,” she admitted. “We were too busy running for safety.”

So the Voidbringers hadn’t anticipated that storm’s arrival either. Kaladin winced, trying not to dwell on how many people had likely been lost to the impact of the stormwall.

“Do better,” he said to her. “These people are your charge now. You’ve seized the city, taken what you want. If you wish to claim any kind of moral superiority, treat your captives better than they did you.”

“Look,” the parshwoman said. “Who are you? And why—”

Something large crashed into Kaladin, tossing him backward into the wall with a crunch. The thing had arms; a person who grasped for his throat, trying to strangle him. He kicked them off; their eyes trailed red.

A blackish-violet glow—like dark Stormlight—rose from the red-eyed parshman. Kaladin cursed and Lashed himself into the air.

The creature followed.

Another rose nearby, leaving a faint violet glow behind, flying as easily as he did. These two looked different from the one he’d seen earlier, leaner, with longer hair. Syl cried out in his mind, a sound like pain and surprise mixed. He could only assume that someone had run to fetch these, after he had taken to the sky.

A few windspren zipped past Kaladin, then began to dance playfully around him. The sky grew dark, the stormwall thundering across the land. Those red-eyed Parshendi chased him upward.

So Kaladin Lashed himself straight toward the storm.

It had worked against the Assassin in White. The highstorm was dangerous, but it was also something of an ally. The two creatures followed, though they overshot his elevation and had to Lash themselves back downward in a weird bobbing motion. They reminded him of his first experimentation with his powers.

Kaladin braced himself—holding to the Sylblade, joined by four or five windspren—and crashed through the stormwall. An unstable darkness swallowed him; a darkness that was often split by lightning and broken by phantom glows. Winds contorted and clashed like rival armies, so irregular that Kaladin was tossed by them one way, then the other. It took all his skill in Lashing to simply get going in the right direction.

He watched over his shoulder as the two red-eyed parshmen burst in. Their strange glow was more subdued than his own, and somehow gave off the impression of an anti-glow. A darkness that clung to them.

They were immediately disrupted, sent spinning in the wind. Kaladin smiled, then was nearly crushed by a boulder tumbling through the air. Sheer luck saved him; the boulder passed close enough that another few inches would have ripped off his arm.

Kaladin Lashed himself upward, soaring through the tempest toward its ceiling. “Stormfather!” he yelled. “Spren of storms!”

No response.

“Turn yourself aside!” Kaladin shouted into the churning winds. “There are people below! Stormfather. You must listen to me!”

All grew still.

Kaladin stood in that strange space where he’d seen the Stormfather before—a place that seemed outside of reality. The ground was far beneath him, dim, slicked with rain, but barren and empty. Kaladin hovered in the air. Not Lashed; the air was simply solid beneath him.

WHO ARE YOU TO MAKE DEMANDS OF THE STORM, SON OF HONOR?

The Stormfather was a face as wide as the sky, dominating like a sunrise.

Kaladin held his sword aloft. “I know you for what you are, Stormfather. A spren, like Syl.”

I AM THE MEMORY OF A GOD, THE FRAGMENT THAT REMAINS. THE SOUL OF A STORM AND THE MIND OF ETERNITY.

“Then surely with that soul, mind, and memory,” Kaladin said, “you can find mercy for the people below.”

AND WHAT OF THE HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS WHO HAVE DIED IN THESE WINDS BEFORE? SHOULD I HAVE HAD MERCY FOR THEM?

“Yes.”

AND THE WAVES THAT SWALLOW, THE FIRES THAT CONSUME? YOU WOULD HAVE THEM STOP?

“I speak only of you, and only today. Please.”

Thunder rumbled. And the Stormfather actually seemed to consider the request.

IT IS NOT SOMETHING I CAN DO, SON OF TANAVAST. IF THE WIND STOPS BLOWING, IT IS NOT A WIND. IT IS NOTHING.

“But—”

Kaladin dropped back into the tempest proper, and it seemed as if no time had passed. He ducked through the winds, gritting his teeth in frustration. Windspren accompanied him—he had two dozen now, a spinning and laughing group, each a ribbon of light.

He passed one of the glowing-eyed parshmen. The Fused? Did that term refer to all whose eyes glowed?

“The Stormfather really could be more helpful, Syl. Didn’t he claim to be your father?”

It’s complicated, she said in his mind. He’s stubborn though. I’m sorry.

“He’s callous,” Kaladin said.

He’s a storm, Kaladin. As people over millennia have imagined him.

“He could choose.”

Perhaps. Perhaps not. I think what you’re doing is like asking fire to please stop being so hot.

Kaladin zoomed down along the ground, quickly reaching the hills around Revolar. He had hoped to find that everyone was safe, but that was—of course—a frail hope. People were scattered across the pens and the ground near the bunkers. One of those bunkers still had the doors open, and a few men were trying—bless them—to gather the last people outside and carry them in.

Many were too far away. They huddled against the ground, holding to the wall or outcroppings of rock. Kaladin could barely make them out in flashes of lightning—terrified lumps alone in the tempest.

He had felt those winds. He’d been powerless before them, tied to the side of a building.

Kaladin… Syl said in his mind as he dropped.

The storm pulsed inside him. Within the highstorm, his Stormlight constantly renewed. It preserved him, had saved his life a dozen times over. That very power that had tried to kill him had been his salvation.

He hit the ground and dropped Syl, then seized the form of a young father clutching a son. He pulled them up, holding them secure, trying to run them toward the building. Nearby, another person—he couldn’t see much of them—was torn away in a gust of wind and taken by the darkness.

Kaladin, you can’t save them all.

He screamed as he grabbed another person, holding her tight and walking with them. They stumbled in the wind as they reached a cluster of people huddled together. Some two dozen or more, in the shadow of the wall around the pens.

Kaladin pulled the three he was helping—the father, the child, the woman—over to the others. “You can’t stay out here!” he shouted at them all. “Together. You have to walk together, this way!”

With effort—winds howling, rain pelting like daggers—he got the group moving across the stony ground, arm in arm. They made good progress until a boulder crunched to the ground nearby, sending some of them huddling down in a panic. The wind rose, lifting some people up; only the clutching hands of the others kept them from blowing away.

Kaladin blinked away tears that mingled with the rain. He bellowed. Nearby, a flash of light illuminated a man being crushed as a portion of wall ripped away and towed his body off into the storm.

Kaladin, Syl said. I’m sorry.

“Being sorry isn’t enough!” he yelled.

He clung with one arm to a child, his face toward the storm and its terrible winds. Why did it destroy? This tempest shaped them. Must it ruin them too? Consumed by his pain and feelings of betrayal, Kaladin surged with Stormlight and flung his hand forward as if to try to push back the wind itself.

A hundred windspren spun in as lines of light, twisting around his arm, wrapping it like ribbons. They surged with Light, then exploded outward in a blinding sheet, sweeping to Kaladin’s sides and parting the winds around him.

Kaladin stood with his hand toward the tempest, and deflected it. Like a stone in a swift-moving river stopped the waters, he opened a pocket in the storm, creating a calm wake behind him.

The storm raged against him, but he held the point in a formation of windspren that spread from him like wings, diverting the storm. He managed to turn his head as the storm battered him. People huddled behind him, soaked, confused—surrounded by calm.

“Go!” he shouted. “Go!”

They found their feet, the young father taking his son back from Kaladin’s leeward arm. Kaladin backed up with them, maintaining the windbreak. This group was only some of those trapped by the winds, yet it took everything Kaladin had to hold the tempest.

The winds seemed angry at him for his defiance. All it would take was one boulder.

A figure with glowing red eyes landed on the field before him. It advanced, but the people had finally reached the bunker. Kaladin sighed and released the winds, and the spren behind him scattered. Exhausted, he let the storm pick him up and fling him away. A quick Lashing gave him elevation, preventing him from being rammed into the buildings of the city.

Wow, Syl said in his mind. What did you just do? With the storm?

“Not enough,” Kaladin whispered.

You’ll never be able to do enough to satisfy yourself, Kaladin. That was still wonderful.

He was past Revolar in a heartbeat. He turned, becoming merely another piece of debris on the winds. The Fused gave chase, but lagged behind, then vanished. Kaladin and Syl pushed out of the stormwall, then rode it at the front of the storm. They passed over cities, plains, mountains— never running out of Stormlight, for there was a source renewing them from behind.

They flew for a good hour like that before a current in the winds nudged him toward the south.

“Go that way,” Syl said, a ribbon of light.

“Why?”

“Just listen to the piece of nature incarnate, okay? I think Father wants to apologize, in his own way.”

Kaladin growled, but allowed the winds to channel him in a specific direction. He flew this way for hours, lost in the sounds of the tempest, until finally he settled down—half of his own volition, half because of the pressing winds. The storm passed—leaving him in the middle of a large, open field of rock.

The plateau in front of the tower city of Urithiru.

Chapter 32

Company

For I, of all people, have changed.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Shallan settled in Sebarial’s sitting room. It was a strangely shaped stone chamber with a loft above—he sometimes put musicians there—and a shallow cavity in the floor, which he kept saying he was going to fill with water and fish. She was fairly certain he made claims like that just to annoy Dalinar with his supposed extravagance.

For now, they’d covered the hole with some boards, and Sebarial would periodically warn people not to step on them. The rest of the room was decorated lavishly. She was pretty sure she’d seen those tapestries in a monastery in Dalinar’s warcamp, and they were matched by luxurious furniture, golden lamps, and ceramics.

And a bunch of splintery boards covering a pit. She shook her head. Then—curled up on a sofa with blankets heaped over her—she gladly accepted a cup of steaming citrus tea from Palona. She still hadn’t been able to rid herself of the lingering chill she’d felt since her encounter with Re-Shephir a few hours back.

“Is there anything else I can get you?” Palona asked.

Shallan shook her head, so the Herdazian woman settled herself on a sofa nearby, holding another cup of tea. Shallan sipped, glad for the company. Adolin had wanted her to sleep, but the last thing she wanted was to be alone. He’d handed her over to Palona’s care, then stayed with Dalinar and Navani to answer their further questions.

“So…” Palona said. “What was it like?”

How to answer that? She’d touched the storming Midnight Mother. A name from ancient lore, one of the Unmade, princes of the Voidbringers. People sang about Re-Shephir in poetry and epics, describing her as a dark, beautiful figure. Paintings depicted her as a black-clad woman with red eyes and a sultry gaze.

That seemed to exemplify how little they really remembered about these things.

“It wasn’t like the stories,” Shallan whispered. “Re-Shephir is a spren. A vast, terrible spren who wants so desperately to understand us. So she kills us, imitating our violence.”

There was a deeper mystery beyond that, a wisp of something she’d glimpsed while intertwined with Re-Shephir. It made Shallan wonder if this spren wasn’t merely trying to understand humankind, but rather searching for something it itself had lost.

Had this creature—in distant, distant time beyond memory—once been human?

They didn’t know. They didn’t know anything. At Shallan’s first report, Navani had set her scholars searching for information, but their access to books here was still limited. Even with access to the Palanaeum, Shallan wasn’t optimistic. Jasnah had hunted for years to find Urithiru, and even then most of what she’d discovered had been unreliable. It had simply been too many years.

“To think it was here, all this time,” Palona said. “Hiding down there.”

“She was captive,” Shallan whispered. “She eventually escaped, but that was centuries ago. She has been waiting here ever since.”

“Well, we should find where the others are held, and make sure they don’t get out.”

“I don’t know if the others were ever captured.” She’d felt isolation and loneliness from Re-Shephir, a sense of being torn away while the others escaped.

“So…”

“They’re out there, and always have been,” Shallan said. She felt exhausted, and her eyes were drooping in direct defiance of her insistence to Adolin that she was not that kind of tired.

“Surely we’d have discovered them by now.”

“I don’t know,” Shallan said. “They’ll… they’ll just be normal to us. The way things have always been.”

She yawned, then nodded absently as Palona continued talking, her comments degenerating into praise of Shallan for acting as she had. Adolin had been the same way, which she hadn’t minded, and Dalinar had been downright nice to her—instead of being his usual stern rock of a human being.

She didn’t tell them how near she’d come to breaking, and how terrified she was that she might someday meet that creature again.

But… maybe she did deserve some acclaim. She’d been a child when she’d left her home, seeking salvation for her family. For the first time since that day on the ship, watching Jah Keved fade behind her, she felt like she actually might have a handle on all of this. Like she might have found some stability in her life, some control over herself and her surroundings.

Remarkably, she kind of felt like an adult.

She smiled and snuggled into her blankets, drinking her tea and—for the moment—putting out of her mind that basically an entire troop of soldiers had seen her with her glove off. She was kind of an adult. She could deal with a little embarrassment. In fact, she was increasingly certain that between Shallan, Veil, and Radiant, she could deal with anything life could throw at her.

A disturbance outside made her sit up, though it didn’t sound dangerous. Some chatter, a few boisterous exclamations. She wasn’t terribly surprised when Adolin stepped in, bowed to Palona—he did have nice manners— and jogged over to her, his uniform still rumpled from having worn Shardplate over it.

“Don’t panic,” he said. “It’s a good thing.”

“It?” she said, growing alarmed.

“Well, someone just arrived at the tower.”

“Oh, that. Sebarial passed the news; the bridgeboy is back.”

“Him? No, that’s not what I’m talking about.” Adolin searched for words as voices approached, and several other people stepped into the room.

At their head was Jasnah Kholin.

The End of Part One

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC

Only one week left! The hype is real :)

Final part before release. So excited to read.

Yaaaay. Just a week till its released.

Only a week left! And NEW chapters :D!

Whoa! One more week! Don’t know how people have held out from these released chapters — they’re just so good!

Jasnah’s back!!!

Jasnah! So happy to see her!

I just wanted to be involved.

Those. Last. Six. Words.

One week, oh boy.

Kaladin I LOVE you.